Originally published in The Helsinki Notebooks: Global Dispatches against Fascism and the Far Right

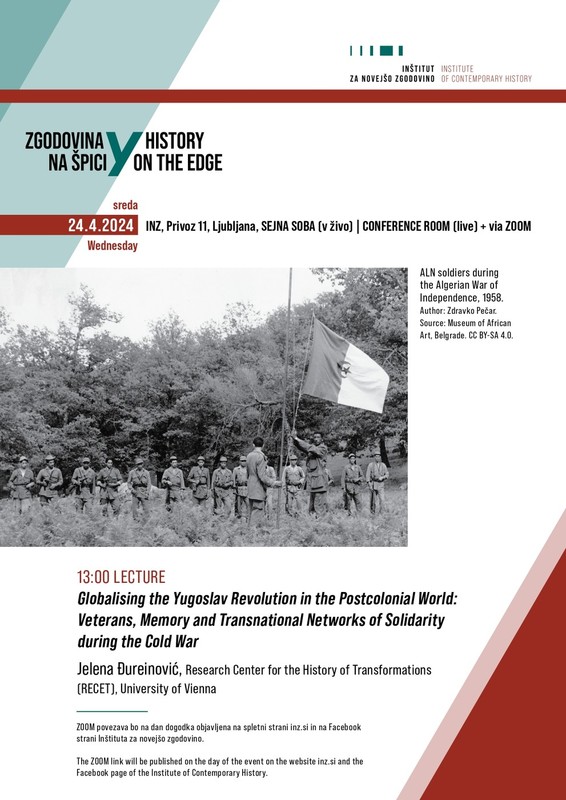

The People’s Liberation War (Narodnooslobodilački rat, NOR), as the Yugoslav Partisans’ antifascist struggle and parallel socialist revolution during World War II were officially termed, was the birthplace of Yugoslav state socialism. The communist-led and country-wide uprising of 1941 rapidly grew into a mass movement and an organised army with large popular support by the war’s end. After the war, the antifascist and revolutionary war became the main source of legitimacy for socialist Yugoslavia and the focal point of the multifaceted memory culture that blossomed over decades.[i]

World War II in Yugoslavia was a war of occupation and liberation, but also a civil war where different forces fought with or against the Axis forces and against each other.[ii] In this context, the Partisans represented the only consistently antifascist movement, building on the interwar experiences of underground operation in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the Spanish Civil War and internationalism. They were also the only political and military force in Yugoslavia that clearly identified itself as antifascist.

As Yugoslavia disintegrated through armed conflicts in the 1990s, the emerging nation-states’ political elites hurried to free themselves from the legacies of socialist Yugoslavia. The People’s Liberation War, as the symbol of Yugoslavia, became the subject of radical revision in the often-parallel processes of erasure, demonisation, inversion and appropriation. At the same time, the governments, right-wing political parties and groups and historians have invested enormous efforts in the rehabilitation of Partisans’ enemies and defeated forces of WWII, recasting them into national heroes and innocent victims of communism because of the executions and trials at the end and after the war. The postwar retribution has served as a narrow lens of interpreting WWII and decades of state socialism, criminalising the Partisans as perpetrators and replacing the narrative of the liberation from fascism into stories of executions, trials and repression. Post-Yugoslav anti-communist memory politics built its legitimacy on the anti-totalitarian stance of the European Union, which “has been instrumental in downplaying and erasing Yugoslavia, the trans-ethnic liberation of the region during the Second World War, and 50 years of peaceful coexistence among former Yugoslav republics”.[iii] In Serbia, the tale of the two Serbian antifascist movements reinvented the collaborationist Chetnik movement as antifascist, even if they had never called themselves that.[iv]

In Serbia since the early 1990s, the memory of antifascism has gone through stages of revision: the appropriation of the Partisans by the regime of Slobodan Milošević in the 1990s, their criminalisation and parallel rehabilitation of the Chetniks as antifascists in the 2000s and, since 2012, the reemergence of large-scale official celebrations of antifascism. In the official discourses that dominate society, the interpretation of the Partisans has traveled from their portrayal as Serbs to communist perpetrators and, most recently, back to their celebration as a victorious Serbian army.[v] The state-sponsored celebrations of the victory and liberation that are a regular practice today coopt the People’s Liberation War, depoliticising, ethnicising and de-Yugoslavising it. The hijacking of the antifascist struggle by the right-wing political elites comes as a bigger surprise than the anti-communist demonisation of it, but it goes hand in hand with the populist rhetoric of Serbia’s current regime and its close affiliation with Russia, where the official memory culture glorifies the Great Patriotic War and the victory against fascism.[vi]

Across the post-Yugoslav space, whether the political actors criminalise or appropriate the People’s Liberation War, the common denominator of post-socialist politics of memory of antifascism is the erasure of its emancipatory and revolutionary dimension. It goes hand in hand with the physical disappearance and disregard for the Yugoslav antifascist memory culture, that takes place parallel to the global hype surrounding the Partisan monuments, which is equally depoliticising and deprived of meaning.[vii] In the spaces of leftist activism and private memories across the region that used to be socialist Yugoslavia, however, the People’s Liberation War still serves as inspiration.

[i] Sanja Horvatinčić and Beti Žerovc, Shaping Revolutionary Memory: The Production of Monuments in Socialist Yugoslavia (Ljubljana, Berlin: Igor Zabel Association for Culture and Theory, Archive Books, 2023); Nikola Baković, Brotherhood on the Move: Ritual Mobilities in the Second Yugoslavia (Zagreb: Srednja Europa, 2023); Heike Karge, Steinerne Erinnerung – versteinerte Erinnerung? Kriegsgedenken in Jugoslawien (1947-1970) (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2010).

[ii] Tea Sindbæk, Usable History? Representations of Yugoslavia’s Difficult Past from 1945 to 2002 (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2012), 192.

[iii] Ana Milošević and Tamara Pavasović Trošt, ‘Introduction: Europeanisation and Memory Politics in the Western Balkans’, in Europeanisation and Memory Politics in the Western Balkans (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), 6.

[iv] Jelena Đureinović, The Politics of Memory of the Second World War in Contemporary Serbia: Collaboration, Resistance and Retribution (London and New York: Routledge, 2020).

[v] M. Beljan, ‘Vučić: Slavimo Dan pobede jake, pobedničke Srbije’, Blic, 5 September 2015, https://www.blic.rs/vesti/politika/vucic-slavimo-dan-pobede-jake-pobednicke-srbije/h9r6sxl.

[vi] Tatiana Zhurzhenko, ‘Russia’s Never-Ending War against “Fascism”. Memory Politics in the Russian-Ukrainian Conflict’, Eurozine, 8 May 2015, https://www.eurozine.com/russias-never-ending-war-against-fascism/.

[vii] Vladimir Kulić, ‘Orientalizing Socialism: Architecture, Media, and the Representations of Eastern Europe’, Architectural Histories 6, no. 1 (2018), https://doi.org/10.5334/ah.273.